On Location 2025

DISLOCATED is a travel-based course (May 13-30, 2025) that explores that difficult history by means of immersive exploration of the cultural and material landscapes of Japanese American incarceration, giving special attention to the problems of memory associated with these events.

DISLOCATED: Memory, Forgetting, and the Landscapes of Japanese American Incarceration

“…I hope this uniquely American story will serve as a reminder to all those who cherish their liberties of the very fragility of their rights against the exploding passions of their more numerous fellow citizens, and as a warning that they who say that it can never happen again are probably wrong.”

– Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Years of Infamy

Mr. and Mrs. K. Iseri have closed their drugstore in preparation for

the forthcoming evacuation from their ‘Little Tokyo’ in Los Angeles.

2023 marked the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans on U.S. soil––an action that Roosevelt authorized under political pressure, ostensibly in the name of national security.

This “uniquely American” episode, as survivor Michi Nishiura Weglyn once called it, deserves fuller acknowledgement than it has generally been given––perhaps especially now, in a period of intensifying nationalist rhetoric, racialized attacks on immigrants, and calls for mass deportation and armed defense of the U.S. border.

Anyone who thinks that such actions are unlikely to happen again or impact their communities, as another survivor, Star Trek actor / activist George Takei has noted in recent days, should recall that two-thirds of the 120,000 WWII incarcerees were naturalized citizens. For many of them, the experience of radical dislocation and imprisonment––which in many cases led to the loss of everything—homes, livelihoods, and communities, even family pets––represented a foundational trauma which has had a long and complex aftermath.

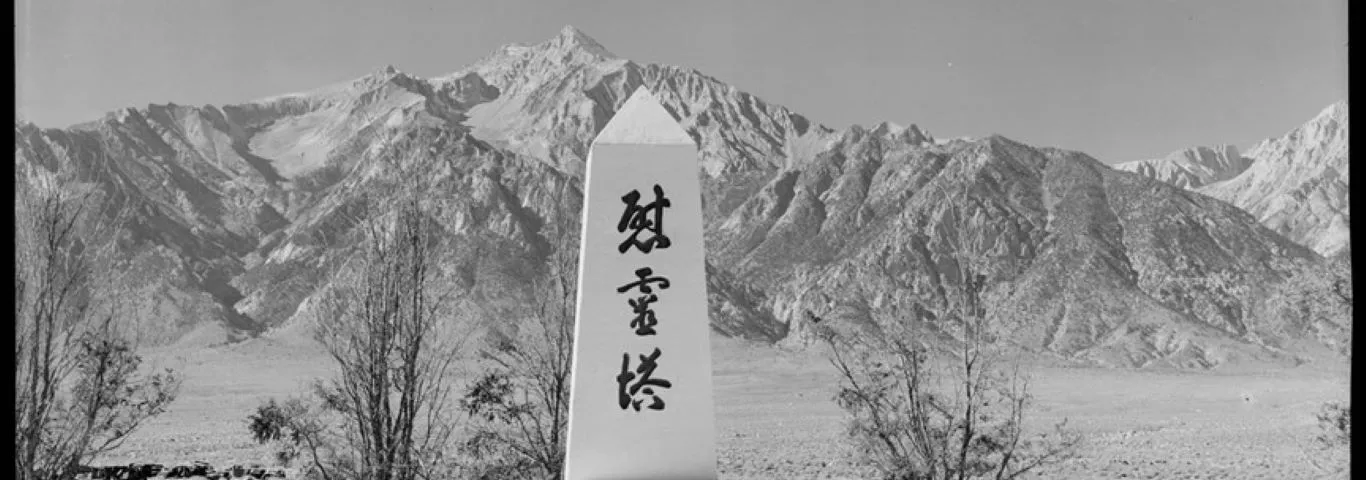

Much of the evidence of the incarceration has been covered up, both literally (as detention centers and prison barracks have been plowed under) and figuratively (as the events have been concealed, denied, or willfully forgotten). History books make only passing mention of the episode, and generally neglect the harms and losses of imprisonment, and few communities beyond the west coast have memorials or exhibitions devoted to the internment. However, important interventions have been made by such institutions as the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) and the DENSHO archive, and the public can now visit remnants of former prison sites.

COURSE DATES: MAY 13 - 30, 2025

We will begin our exploration with a brief introductions and visits to relevant sites in St. Louis, before traveling to California. Along the way, we will visit many other places––marked and unmarked, official and unofficial, visible and invisible––associated with Japanese American immigration, identity, and the incarceration experience, including several in San Francisco. We will seek out sites of community resistance, resilience, memory, and memorialization, from revered institutions (e.g. the Japanese American National Museum, National Japanese American Historical Society, and the UC-Berkeley / Bancroft Library) to grass-roots-sponsored initiatives as well as sites and popular heritage / tourist destinations (e.g. Angel Island, Japantown, former Tanforan Assembly Center).

Students will pursue collaborative site-based investigations of the cultural landscape, making frequent reference to local experts and guest speakers, archival, ethnographic, and visual evidence, and the elements of the built environment. This work will also be informed by methods / readings drawn from diverse disciplines, including social history, archaeology, geography / landscape studies, architectural history, design, cultural / ethnic studies, and others; as well as from by the stories of survivors and work of memory activists, psycho-social studies of the traumatic effects of incarceration; and arts-based efforts to uncover these suppressed histories. We will also give consideration to the political climates and context of the broader phenomenon of collective forgetting––during both the periods in question, and in our own time.

ON LOCATION 2025 INSTRUCTORS

Heidi Aronson Kolk

Heidi Aronson Kolk

Assistant Professor; Assistant Vice Provost for Assessment, Office of the Provost

Heidi Aronson Kolk is a cultural historian who began academic life as a visual artist and poet, pursued graduate study in literary history and American culture studies, and now teaches in WashU’s College & Graduate School of Art, in particular the MFA in Illustration & Visual Culture program.

Kelley Van Dyck Murphy

Assistant Professor; Co-Director, Fox Fridays

Kelley Van Dyck Murphy is an assistant professor of architecture at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. Her research explores themes of identity, authorship, and context through an investigation of how materiality is entwined with larger cultural narratives.