In the days following Michael Brown's death, the QuikTrip on West Florissant Avenue served as a hub of political activity, including gatherings in which community members expressed anger and sorrow, solidarity and resistance. Although claims that Brown had robbed the convenience store before his death were proven false, people continued to gravitate to the site. It had been a well-trafficked place of business before the rioting, and now it offered a high degree of visibility, for media attention was glued there. Even when police stepped up security measures, resorting at times to rubber bullets and tear gas -- even as the building began to disintegrate -- people came by the thousands. Indeed, these grim realities seem only to have reinforced the site's symbolic power.

Some of this power was initially achieved through early acts of site-marking -- efforts made by members of the public to demarcate and define the QT to give it new meaning and use. Spontaneous vigils and protests in the hours after Brown's death were the first of these; they called attention to the community's aggrieved state through disruptive human presence and signage. These were followed by site-marking in the form of memorialization -- chanting, singing, dancing, more sign-posting -- as well as defacement.

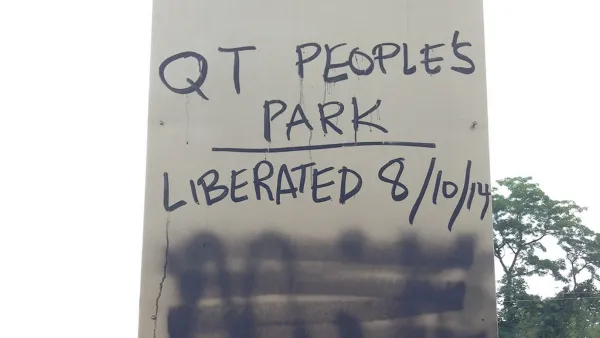

Such site-marking altered the QT's physical appearance and perceived purpose. It was no longer a convenience store, for its signs had been pulled down or tagged with graffiti and its commercial life radically foreshortened. Many condemned this site-marking activity as destruction of private property, but some viewed it as a kind of symbolic consecration -- the ritual calling forth of new life, new forms of community, and healing, through loss. The day after the fire, someone with a black marker christened the site a "QT PEOPLE'S PARK | LIBERATED 8/10/14."

Graffiti listing historic

episodes of civil unrest

The allusion to People's Park was at once playful and serious. It marked the QT as an unlikely public space whose fate, like that of its UC-Berkeley counterpart, was both contested and uncertain. It also placed the Ferguson rioting and protest in a larger narrative of civil unrest, much like the signs that placed the names of other victims of police brutality alongside Michael Brown's -- or the graffiti that included Ferguson in a list of historic episodes of civil unrest, including Spain '36, Watts '65, L.A. '92, and Cairo '11. In so doing, it urged further political awakening amongst those who may not have considered the broader implications of their actions in the QT parking lot.

Other forms of site-marking went beyond acknowledgement of the QT's significance as public space, attempting to define and delimit its use. Through clean-up of the graffiti and clearing of the rubble, for example, some residents reasserted "civility" and imposed order at the site. Police used yellow CAUTION tape to bound and manage the site in another way -- by declaring the store and its environs a no-go zone, a crime scene, and perhaps by implication (the media had already begun to use the phrase) a "ground zero" of Ferguson unrest. And some seemingly destructive acts -- the dismantling of QT signage, for example, and the inscribing of walls and pavement with graffiti -- policed the site through repurposing private property for public use. The innovator of the "QT PEOPLE'S PARK" slogan positioned it on a tall, recently-denuded QT sign (just above spray-painted graffiti that had been crossed out that read, simply, "Mike").

The naming of the site as a "QT PEOPLE'S PARK" turned out to be more than just poetically apt, for its contested nature has come to mirror that of Berkeley's People's Park in several ways. Like the People's Park, Ferguson's now-derelict convenience mart has given material expression to the struggle to claim public space in a tightly-managed suburban landscape that discourages politicized behavior and disorder of any kind. Fundamentally, site-marking practices have acknowledged competing claims on public space -- for example, anti-police graffiti on the QT were quickly covered over with black spray paint and hand-written signs. This has looked very similar to efforts by activists and locals, including homeless people, who have used graffiti and other forms of "desecration" to argue that Berkeley's People's Park should remain open to disordered political expressions.

As the People's Park was for the homeless, who have been kicked out of every other public space in Berkeley, the QT was the only space some people had. At the time of its closing, a Missouri State senator explained to the Washington Post that protestors and some residents really "have no other place, so they've made it their own." Of course, the QT People's Park has been closely monitored by law enforcement and the site's owners, who, like their counterparts at the Berkeley People's Park, quickly set about managing its messages and uses, and eventually fencing off the site to "protect the public." In spite of this, the QT achieved temporary status as an unruly public space where people could gather without mediation by the state -- as unlikely a public square as the McDonald's down the street, and one with more staying power in the public imagination.

sources

"Death in the Suburbs: Why Ferguson's tragedy is America's story"

Don Mitchell, "The End of Public Space? People's Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy" (Annals of the Association of American Geographers 85:1 (108-133).

Wesley Lowery. "The QuikTrip gas station, Ferguson protesters' staging ground, is now silent"

Photo credit: Tara Pham

Inscription on vandalized Ferguson QuikTrip signage: "QT PEOPLE'S PARK" | "LIBERATED 8/10/14".